Napoleon’s Spanish War

“Atlas histórico de España”, Enrique Martínez Ruiz, Consuelo Maqueda Abreu, Emilio de Diego, Ediciones Istmo, 2016

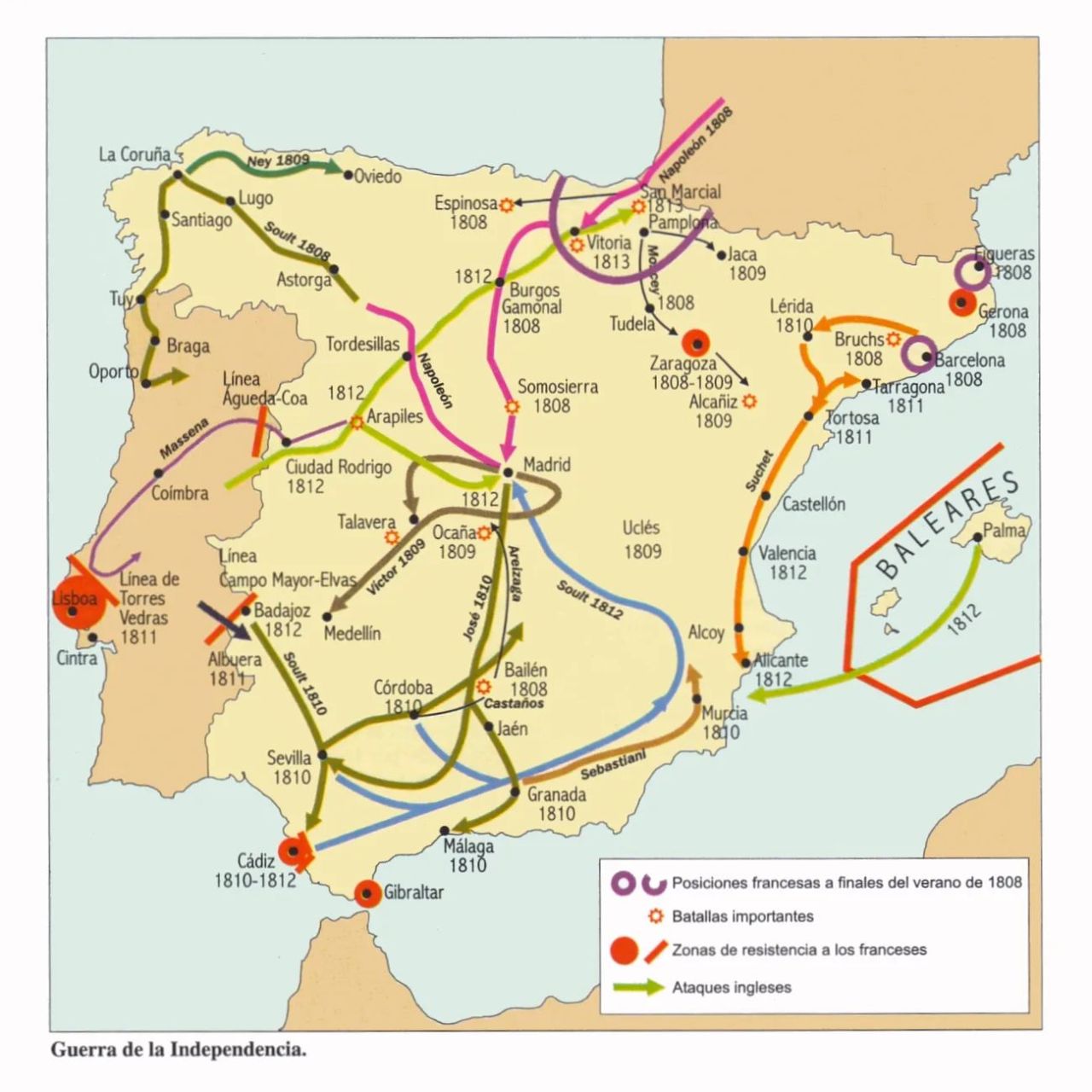

For Napoleon, the Iberian Peninsula was a weak link in the southern flank of the continental blockade. In 1807, he sent Junot to occupy Portugal, where smuggling of British products was developing on a large scale. The presence of French garrisons on Spanish territory exacerbated the dynastic crisis which undermined power, torn between King Charles IV, Prime Minister Godoy and Infante Ferdinand. Napoleon deposes the Bourbons, exiled in France and replaced by Joseph Bonaparte. A popular riot broke out in Madrid on May 2, 1808, followed by fierce repression on the 3rd. The country was set ablaze, resistance was organized by politico-military juntas. French troops were defeated at Bailén, in Andalusia, in July 1808. Napoleon had to strip the eastern front to undertake costly reconquest operations.

In the years that followed, Spain became a gigantic battlefield. Spanish resistance is composite; a strong Catholic component gave the conflict the appearance of a crusade, while the politicians were divided between dynastic loyalty to the “legitimate” king, Ferdinand VII, and liberal aspirations which were expressed in the Constitution of Cádiz of 1812. The supporters of “Intruder king”, the “josefinos”, are isolated and only provide a semblance of authority under the cover of powerful military governors, Soult in the south, Suchet in the north. The French and their allies know how to play on the divisions of their adversaries, the liberals wary of the bands of partisans often supervised by priests and fanatically devoted to Ferdinand, whose absolutist tendencies are a mystery to no one.

It was the English expeditionary force commanded by Lord Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, hostile to the people’s war, which ultimately decided the balance of power. In June 1813, the French army was crushed in Vitoria and had to evacuate the peninsula.